The doctrine of Grace has been watered down by religion - because real grace is a hard pill to swallow.

Grace and the notion that something is given randomly, freely and without justification offends human ideas around justice and never more so than in modern times when more than ever, humans are focused on ideas of justice and human rights.[1]

Justice doesn’t just factor into our politics, it factors heavily into cultural and religious ideas of good and evil.

I’m not saying I’ve got anything against justice — I’ve always been oriented toward what is fair (maybe too much).

But ideas like good comes to those who earn it or bad comes to evildoers just isn’t what Jesus was trying to get at. In Matthew 20, we read a parable told by Jesus about laborers who worked unequal time and got paid equally. In Luke 15, we read a parable told by Jesus about a son who sins and is still welcomed and celebrated by his father.

We’ve heard those parables a hundred times. We recognize they are about grace and can see how they were meant to confront ideas of God demanding a quid-pro-quo, and yet strangely, Christian doctrine and practice is shot through with shame and punishment for sin and reward for goodness. In the area of grace, Christianity looks less like Christ and more like the courts.

The apostle Peter talks about how the goodness of God can undo shame in the following:

2 Like newborn infants, long for the pure, spiritual milk, so that by it you may grow into salvation3 if indeed you have tasted that the Lord is good.

4 Come to him, a living stone, though rejected by mortals yet chosen and precious in God’s sight, and 5 like living stones let yourselves be built into a spiritual house, to be a holy priesthood, to offer spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus Christ. 6 For it stands in scripture:

“See, I am laying in Zion a stone,

a cornerstone chosen and precious,

and whoever believes in him will not be put to shame.”

7 This honor, then, is for you who believe, but for those who do not believe,

“The stone that the builders rejected

has become the very head of the corner,”

8 and

“A stone that makes them stumble

and a rock that makes them fall.”

They stumble because they disobey the word, as they were destined to do.” (1 Peter 2:2-8, NRSVUE)

I used to read this to mean that those who believe in Jesus would not be put to shame and those who don’t believe in Jesus - those who reject Jesus - those who disobey Jesus - will stumble. They WILL be put to shame.

But is that really it? That seems a little at odds with the prodigal son story doesn’t it?

Maybe the key is to ask just exactly who and what is this cornerstone we are believing in? Sure, it’s Jesus, but what does that mean? What if the cornerstone that is Jesus is the cornerstone of grace? The Jesus who did not judge the woman caught in adultery . The Jesus who welcomed the prodigal with a feast. The Jesus who told the thief on the cross he would be with him in paradise. The Jesus who ate with tax collectors, prostitutes, “sinners.” The Jesus who said he did not come to judge the world.

The Jesus who was grace living and breathing. What else could undo shame better than that Jesus? The Jesus of grace?

But THAT’s a Jesus people stumble over.

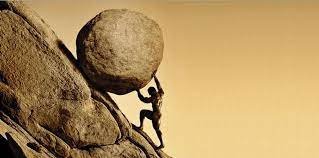

People like a loving Jesus. They like a kind Jesus. They even like the Jesus who turns over tables and whips the temple back into shape. But it’s harder to like the Jesus who lets people off the hook. It’s hard not to stumble on the idea that I might work a full day and get the same pay as the slacker who shows up at 4:45 and puts in 15 minutes. It’s hard not to stumble on the idea that I might live a good life and get the same blessings from God as the guy who is an asshole or worse.

That’s offensive. It’s a stumbling block.

And it’s the very cornerstone of the gospel. Grace.

And Christianity has missed it.

[1] Charles Taylor. Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity. (Cambridge Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 1989), 11.